You can’t have consumer privacy without having strong website identity

Today there’s a huge wave toward protecting consumer privacy – in Congress, with the GDPR, etc. – but how can we protect user privacy on the web without establishing the identity of the websites that are asking for consumer passwords and credit card numbers? Extended Validation (EV) certificates provide this information and can be very useful for consumers.

Recently, Google and Mozilla have announced plan to eliminate the distinctive indicators in the Chrome and Firefox browsers that let consumers know that they are looking at a site authenticated with an EV certificate. We believe this is a mistake – and would like to see Mozilla and Google work to come up with innovative ways to use EV data – rather than hide it from view.

This is an important story about identity and privacy on the web.

For about ten years, websites that want to show users their confirmed identity have gone through the Extended Validation (EV) process when buying SSL/TLS certificates from their Certificate Authorities (CAs). The process involves multiple steps, modelled after banking “know your customer” rules. Extended Validation includes confirming that the organization that controls the certificate’s domain is duly incorporated and in good standing, taking steps to confirm it is a “real business”, confirming its business address and phone number, and confirming the authority of the person ordering the certificate. This confirmed identity information is then inserted in the EV certificate, and is cryptographically signed it so it can’t be altered or imitated by fraudsters.

Each EV certificate includes a wealth of information on the organization behind the website. As an example, here is an EV certificate issued to Bank of America:

CN = www.bankofamerica.com

SERIALNUMBER = 2927442

2.5.4.15 = Private Organization

O = Bank of America Corporation

1.3.6.1.4.1.311.60.2.1.2 = Delaware

1.3.6.1.4.1.311.60.2.1.3 = US

L = Chicago

S = Illinois

C = US

This information shows that Bank of America is a Delaware, US corporation with Delaware corporate registry number 2927442, and has a confirmed business location in Chicago. This information unambiguously identifies the organization that controls the website www.bankofamerica.com, and gives the world (users, law enforcement, etc.) contact information and even potential recourse in the event anything bad happens on the website. All CAs in the world follow the same EV validation processes, and insert identity information in EV certificates in the same way. The process has been standardized under Extended Validation Guidelines developed and maintained by the CA/Browser Forum.

Many major enterprises – including banks, financial institutions, hospital centers, and more – use EV certificates to protect their customers and their brands from the many phishers who try to imitate them.

The main alternative to EV certificates are domain validated (DV) certificates, which contain no identity information.

DV certificates only confirm that the website owner controls the domain in the DV certificate. In many cases, the issuing CA has no idea who the website owner is, and often has no ability to contact the owner! Here is all of the identity information in the DV certificate for the website whoami.com:

CN = whoami.com

For the past decade, browsers have distinguished websites that use EV certificates with a distinctive EV user interface (UI), so users can know that the website owner’s identity has been strongly confirmed by a third party CA. As a result, there is almost no phishing on sites with EV certificates, while phishers have migrated to encryption using anonymous DV certificates – and phishing on DV sites has skyrocketed.

Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox Will Soon Eliminate the Current EV UI

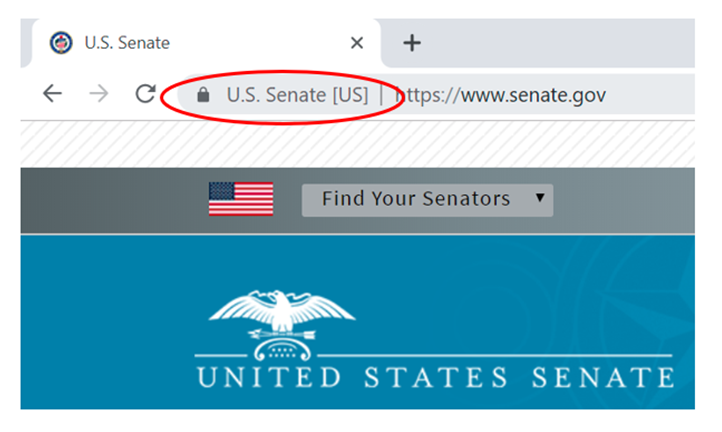

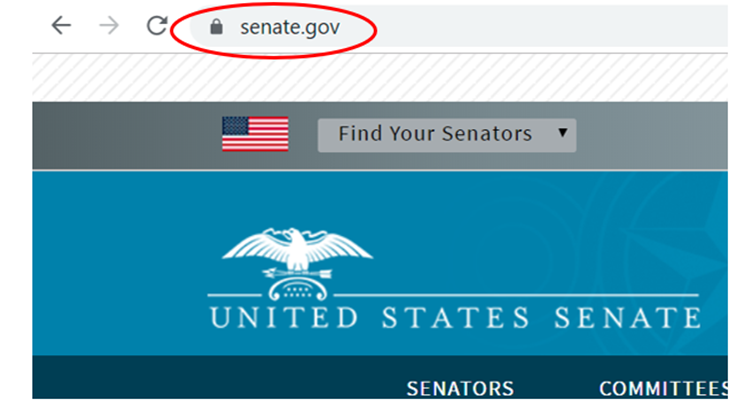

Unfortunately, Google Chrome has announced it will eliminate the distinctive EV user interface with the next version of its browser, Chrome 77, effective in mid-September 2019; Mozilla will do the same in October. After this change, users will only see a site’s URL, the same as for DV sites. Here are before-and-after examples of the user interface – in this case, for the United States Senate’s website, which uses an EV certificate.

Before – in Google Chrome 76

After – in Google Chrome 77

Before – in Firefox 69 for GitHub, with a green indicator for EV authentication:

Before – in Firefox 69 for GitHub, with a green indicator for EV authentication:

We believe this is an unwelcome change, being made based on mistaken or incomplete analyses of the benefits of strong website identity markers.

Here are the reasons why we believe Google and Mozilla should reverse their decisions and restore website identity in their EV UIs to improve security for users and others.

Phishing on DV sites is skyrocketing. Users are safer on sites with EV certificates.

Until recently almost all phishing and malware was on unencrypted http sites. They received a neutral UI, and the bad guys didn’t have to spend time and money getting a certificate, even a DV certificate, that might leave traces as to their identity. Users were trained (and remembered the training) to “look for the lock symbol” for greater security.

Then a few things happened: (1) Google incentivized all websites to move to encryption through the use of its “Not secure” warning, (2) Mozilla instituted a similar “Not Secure” warning, and (3) Let’s Encrypt began offering anonymous, automated DV certificates to everyone, including known phishing sites, in part through Platinum-level financial support from Mozilla and Google.

Predictably, virtually all phishing has now moved to DV encrypted websites, which receive the lock symbol on web browsers. In fact, the FBI just issued a warning to consumers not to no longer trust the https or lock symbol in browsers as half or more of phishing sites now display the lock symbol.

Browsers haven’t yet caught up with this. Browser phishing filters such as Google Safe Browsing are good but not perfect. According to the most recent NSS labs report issued in October 2018, Google Safe Browsing offers only about 79% user protection at “zero hour”, gradually rising to 95% protection after two days. However, most phishing sites are shut down within two days – meaning that thousands of users could be harmed before a site is flagged for phishing.

That’s where EV certificates can help. Websites with EV certificates have a very low incidence of phishing. New research from RWTH Aachen University recently presented at Usenix measured the incidence of phishing sites using certificates of various validation levels. EV certificates made up 0.4% of the total population of phishing sites with certificates but 7% of the “benign” (non-phishing) sites. Compare that to OV, where 15% of phishing sites had that certificate type and 35% of benign sites had the same. And compare that again to Let’s Encrypt certificates, which made up 34% of certificates for phishing sites and only 17% for benign sites.

This research validates the results of an earlier study of 3,494 encrypted phishing sites in February 2019. In this study the distribution of encrypted phishing sites by certificate type was as follows:

EV 0 phishing sites (0%)

OV 145 phishing sites (4.15%)*

DV 3,349 phishing sites (95.85%)

*(These phishing OV certs were mostly multi-SANs certs requested by CDNs such as Cloudflare containing multiple URLs for websites whose content the Subject of the OV cert did not control. Perhaps such certificates should be DV rather than OV.)

Furthermore, research from Georgia Tech shows that EV sites have an exceedingly low incidence of association with malware and known bad actors.

In plain terms, users are safer when they visit sites with EV certs – and it benefits users to let them know.

The idea that users don’t act on positive security indicators misses the mark.

The browser companies have stated that because end users don’t understand the EV marks on the browser, and don’t act on them, that they are unnecessary – and can be replaced only by a positive indicator of unsafe – unencrypted – sites.

We think that this analysis misses the following:

- The internet today has a clear signal of a site’s safety for the end user in the EV indicators. Browsers should see this as an opportunity to educate users, not to take away useful information.

- Users are not a single homogenous group, and they don’t all behave the same. Most of the people reading this blog post do, in fact, notice whether or not an EV indicator is there. Providing this evidence to some users is better than providing it to no one.

- User behavior changes based on context. Day to day, a site visitor may suffer from “interface blindness” when everything is going well. But when something suspicious occurs, they become hyper aware. And, the presence of an EV cert gives the likes of law enforcement a clear path forward when pursuing perpetrators of online crime.

- Positive security indicators work in many other contexts where expectations are predictable – and with standards and education would work better in browsers as well. Let’s take an offline example — the seat belt. Most of us expect the feel of a seat belt across their laps and shoulders when in a moving car, and without it we feel uncomfortable. That is a positive security indicator. We miss it when it’s absent is because it is consistent, ubiquitous, obvious, and important to us.

There is no reason why an identity security indicator cannot meet these same criteria. Unfortunately, EV security indicators in browsers have been inconsistent and subject to changes over time, making it hard to successfully educate users. These disadvantages are all addressable, if companies like major browser and OS vendors treat doing so as a priority.

Relying on the URL alone is not sufficient to protect users

Without the EV identity indicator in Chrome or Firefox, users will have to rely on the URL and an interstitial warning, if and when a phishing site is identified. But as Google security researchers have stated, “People have a really hard time understanding URLs. They’re hard to read, it’s hard to know which part of them is supposed to be trusted, and in general I don’t think URLs are working as a good way to convey site identity.”

An EV UI does not require users to scrutinize the URL– — it simply identifies the website owners and assures the users that this site has been authenticated, and is likely to be safe from phishing.

Some opponents of the EV user interface say it should go away because users don’t understand or know how to evaluate the specific organization information that’s displayed.

This is a reason to improve the EV indicator, rather than remove it. An improved EV UI could show an easy to understand “identity/no identity” indicator – a green lock symbol and URL for identity (EV), black for no identity (DV). If users want to see the specific organization information for the identity sites, it can be displayed with one click on the green lock symbol. With a little user training (such as a pop-up for a few months explaining what the green UI means), users benefit from this information.

A distinct EV indicator offers proactive security, while browser phishing filters are retroactive only, meaning some users will get hurt

Having the browsers check the certificate and indicate its status to users is proactive security. In contrast, relying on a browser filter to protect users against phishing is like letting people get on an airplane anonymously, but promising to blacklist any passenger from future flights who sneaks on board with a weapon, and attacks the other passengers. Worse, without certification, the banned phisher can shut down their site and anonymously run the same scam from a new domain – free for from phishing filters for another couple days.

Rewarding identified websites with a distinct EV UI is one way of providing user security proactively, before they provide any personal data to a website.

Phishers won’t start using EV certificates if public recognition of the EV UI increases

Finally, some industry watchers object that if user trust in EV sites increases, then phishers will just start getting EV certificates. That’s possible, but remember: – once a phisher with an EV certificate uses it for an scam, the issuer will likely revoke the certificate and add both the organization’s *name* and its phishing domains to its flag list – and the organization (a specific corporation identified by name, state of incorporation, and serial number) will never be able to get another EV certificate from that CA.

Moreover, CAs are currently setting up a common EV flag list, so that a corporation found to have intentionally engaged in phishing likely won’t be able to get an EV certificate from any other CA. That’s one reason why phishers don’t use EV certificates today – it’s too expensive and time consuming if you can only use your corporation’s EV certificate in one phishing campaign.

Recommendations

We were among the group who put together the original EV specification. At that time, we envisioned EV would be an ongoing, evolving standard that the community continued to make better. Hearing objections about EV being less than perfect, one cannot help but think of the adage about perfect being the enemy of good. EV is good. It’s really good, and the statistics indicate that it is helping make the web a better place. Let’s focus our energy on making it even better.

The CA Security Council believes that the industry should evolve the EV certificate indicators, rather than remove them:

To combat phishing and raise identity standards for websites, we believe the browser companies should work together to develop common security indicators for laptops and mobile devices, and to engage with CAs on user training to help users make good security decisions based on available identity information. Common indicator standards have been extraordinarily successful.

Another example: The automotive stop sign used to vary country by country and state by state before it became standardized. If stop signs were always different and users didn’t know what they meant, then some might argue “Drivers don’t use stop signs to make security decisions (such as stopping their cars), so let’s just remove all stop signs.” This would clearly leave our roads even less secure. As phishing attacks continue to increase and evolve, our identity and security standards – and user education – must as well.

There’s a great opportunity for innovation and collaboration here, that will benefit web users and the whole industry.