As the legendary coach of the NY Yankees Yogi Berra allegedly said, “It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” But we’re going to try.

Here are the CA Security Council (CASC) 2019 Predictions: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

The Good

Prediction: By the end of 2019, over 90% of the world’s http traffic will be secured over SSL/TLS

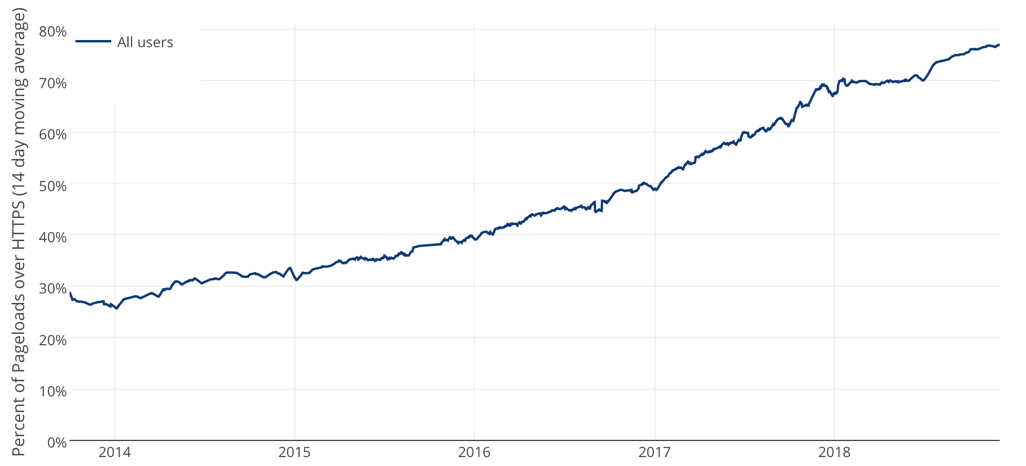

Encryption boosts user security and privacy, and the combined efforts of browsers and Certification Authorities (CAs) over the past few years have moved us rapidly to a world approaching 100% encryption. To date, encryption uptake has resembled a sigmoidal curve, with slow increases in encryption at first, followed by rapid increases in the last two years, followed by a (likely) flattening of the curve as the internet approaches 100% encryption. (In many cases, website owners are driven to encryption by the combination of browser warnings and the availability of free SSL/TLS certificates; in some countries such as China, these factors may not be present and so encryption may lag.)

According to Firefox Telemetry, 77 percent of all page loads via Firefox are now encrypted, and the number continues to rise. Our prediction is that this number will reach 90 percent by the end of 2019.

Prediction: TLS 1.3 will have an impressive growth of over 30% by the end of 2019

TLS 1.3, a critical overhaul of TLS or transport layer security, was approved by the IETF as an official standard last August (RFC 8446) after four years of work. The IETF Task Force responsible for the revision described it as “a major revision designed for the modern Internet,” which contains “major improvements in the areas of security, performance, and privacy.” This upgrade will make it much harder for eavesdroppers to decrypt intercepted traffic – a major driver in the design of the new protocol was the mass surveillance of internet communications by the US National Security Agency (NSA) revealed in 2013 by Edward Snowden. Unlike TLS 1.2, as of today there are no identified security holes in the algorithms used in TLS 1.3.

So what needs to happen now? Implementation, of course. How fast will the use of TLS 1.3 grow? Let’s check the math:

- com states that TLS 1.3 is supported by Chrome versions 56 to 70 and Firefox versions 53 to 63. The other browsers are not currently supporting TLS 1.3

- Chrome and Firefox are between 60 to 80 percent of the browser usage

- Large CDNs such as Cloudflare and Akamai support TLS 1.3

- Netcraft currently states that TLS 1.3 is supported by 6.5 percent of servers and is now growing by close to 1 million sites per month

OK, so maybe it is hard to do the math, but the bottom line is the majority or the browsers support TLS 1.3 and the large CDNs have deployed TLS 1.3 to receive its benefits. We will also expect large cloud providers to support TLS in 2019.

Let’s assume that it will take some time for the traditional web servers to be upgraded to support TLS 1.3, but maybe the browsers will indirectly help with this issue. The browsers have stated that they will stop supporting TLS 1.0 and 1.1 starting in 2020 – this message will likely cause server administrators to turn-off these versions of the protocol. When they do, they just might turn on TLS 1.3.

With the Internet moving to CDNs and cloud providers, the rate of growth of TLS 1.3 will be much faster than the growth to TLS 1.2. With the fact that TLS 1.3 is more secure and more sufficient, we think that its usage will grow to more than 30 percent in 2019.

The Bad

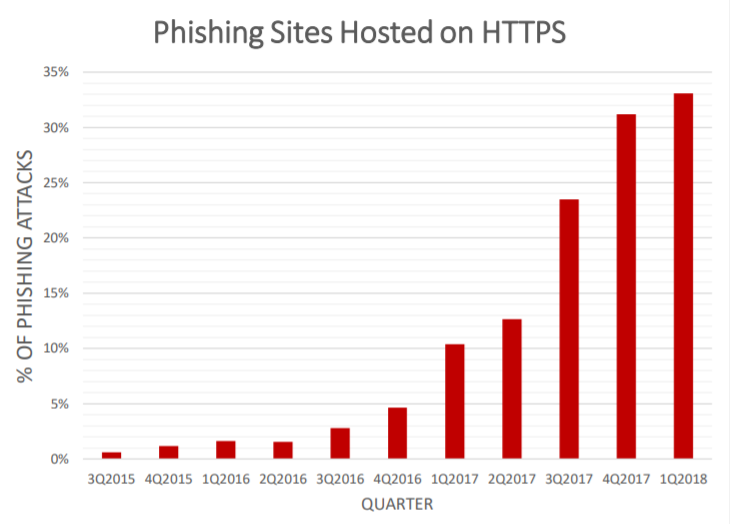

Prediction: Phishing (especially encrypted phishing) will continue to skyrocket

As noted above, websites are moving rapidly to encryption – that’s good. Unfortunately, phishing sites are making the trip to encryption along with legitimate sites – that’s bad. This growth in encrypted phishing has primarily occurred via Domain Validated certificates. These certificates can be acquired via automation, are anonymous (no identity information is required to acquire these certificates). These phishing sites often have look-alike domain names imitating major valid sites for banks, shopping sites, and payment sites (such as login.paypal.com.phishingsite.com) and are intended to trick users into revealing their login and credit card information on realistic looking pages for the real sites.

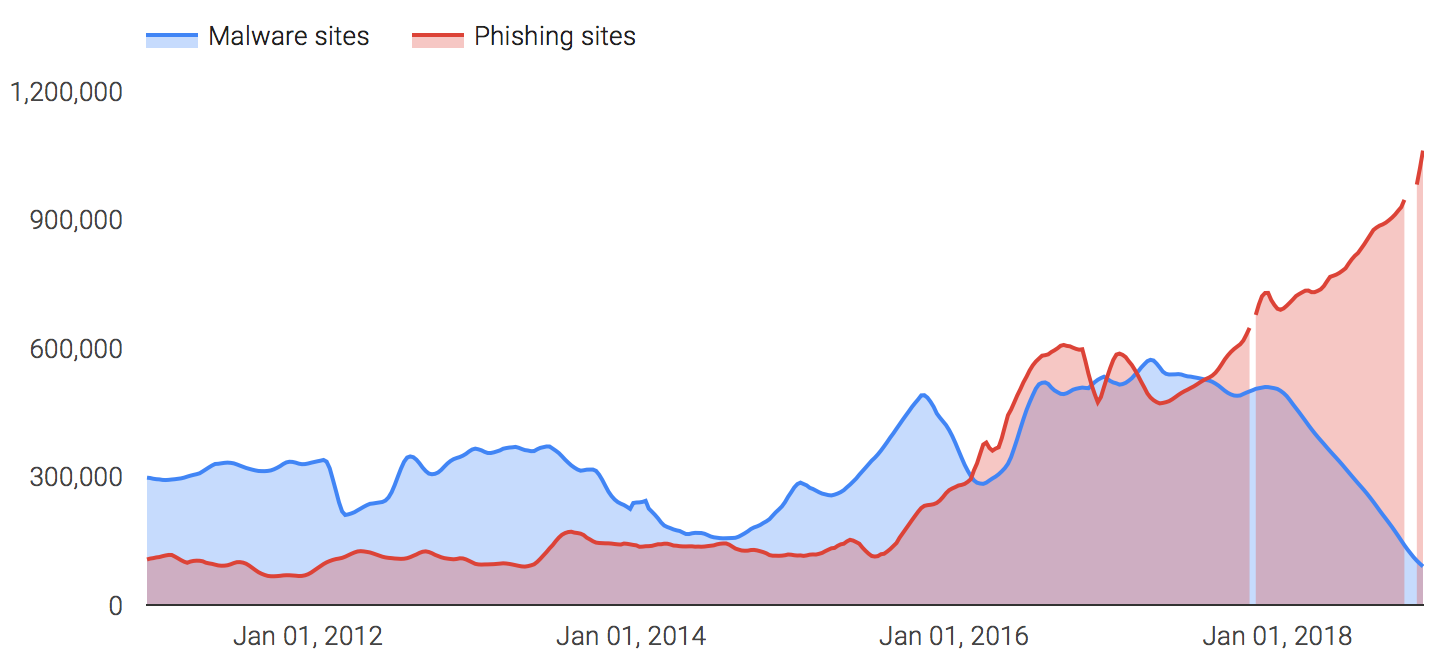

The tables below demonstrate these trends:

Unsafe websites detected per week

Source: <https://transparencyreport.google.com/safe-browsing/overview?unsafe=dataset:1;series:malware,phishing;start:1293840000000;end:1543132800000&lu=unsafe>

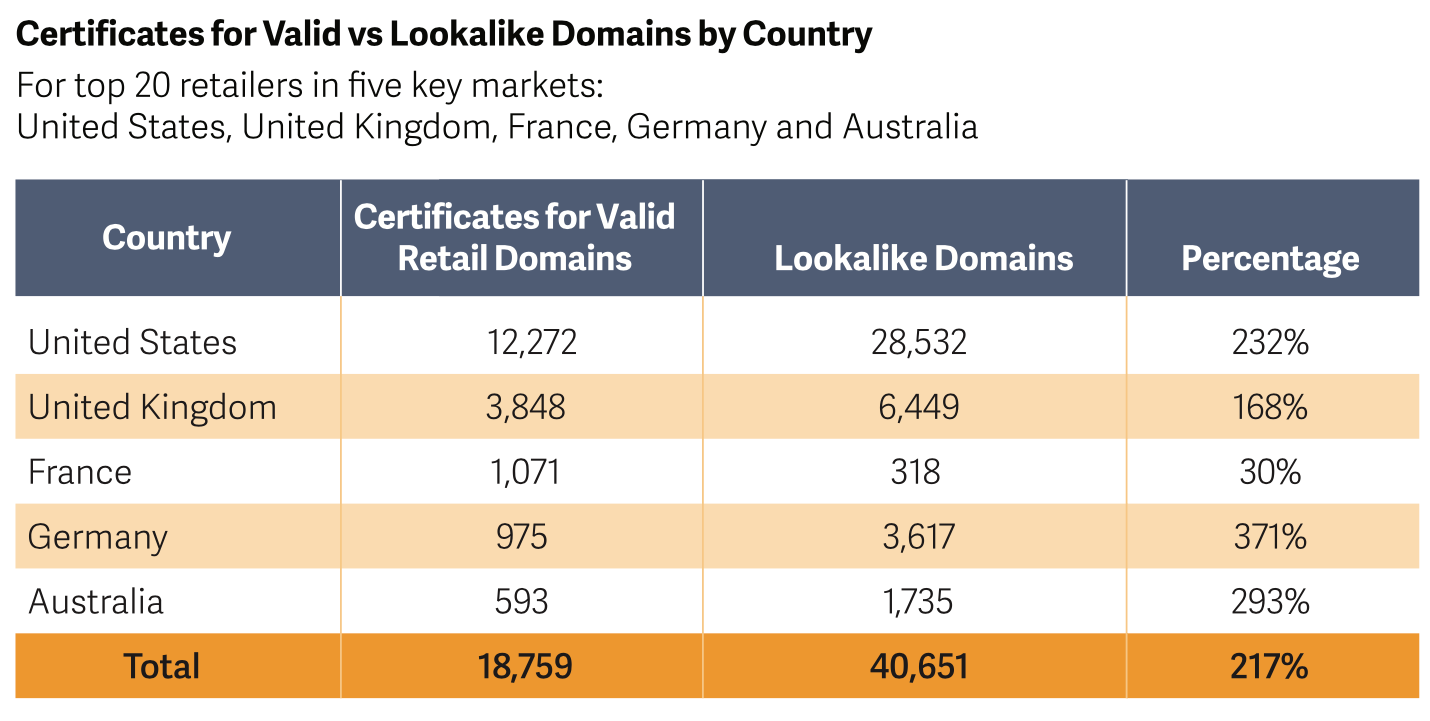

It’s not too dramatic to say there has been an explosion of phishing sites using encryption to trick users. Here are key findings from a recent Venafi study:

- The total number of certificates for look-alike domains _is more than 200% greater _than the number of authentic retail domains.

- Among the top 20 online German retailers, there are almost four times more look-alike domains than valid domains.

- Major retailers present larger targets for cyber criminals. One of the top 20 U.S. retailers has over 12,000 look-alike domains targeting its customers.

- The growth in phishing sites seems to be connected to the availability of anonymous and free TLS certificates called domain validated certificates which make up 98% of phishing sites.

Source: [Venafi](https://www.venafi.com/) Research Brief – <https://www.venafi.com/blog/venafi-retail-research-will-holiday-shoppers-be-duped-look-alike-domains>

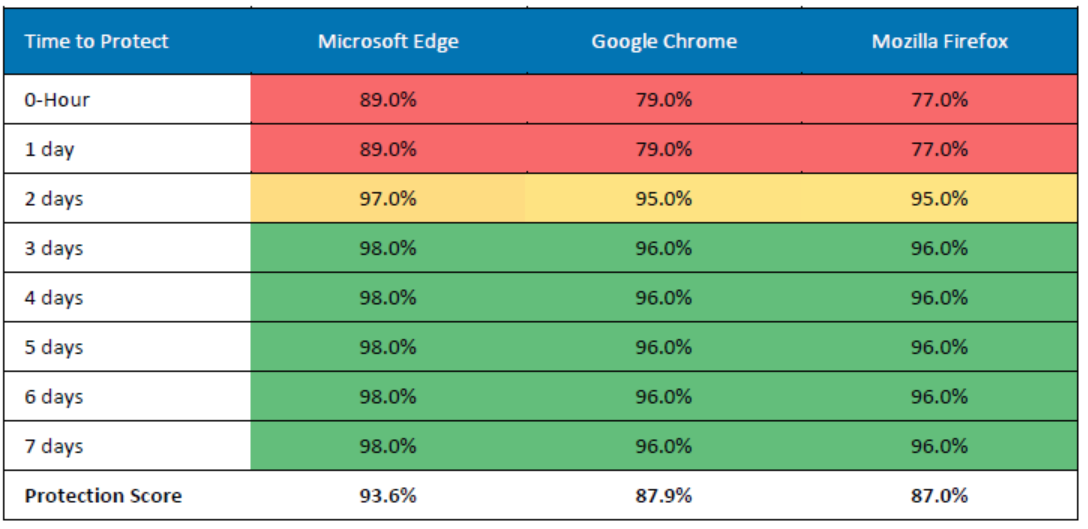

What’s the solution? Unfortunately, there isn’t one at present. While browser filters such as Microsoft Smart Screen and Google Safe Browsing do a good job at detecting many phishing sites, they don’t find them all. The latest studies by NSS Labs shows that it takes two full days for the three leading browser filters to block 95% of phishing sites – in contrast, by Day 1 only 77.0% of phishing sites were blocked by Firefox, 79.0% by Chrome, and 89.0% by Edge.

Source: <https://research.nsslabs.com/reports?cat0=22>

Because most phishing sites are set up and taken down in a matter of hours, not days, this means many thousands of users are not meaningfully protected by browser filters.

We predict the problem of encrypted phishing sites that imitate real websites will get significantly worse in 2019.

Prediction: Users will suffer harm from the divergent UI policies of browsers

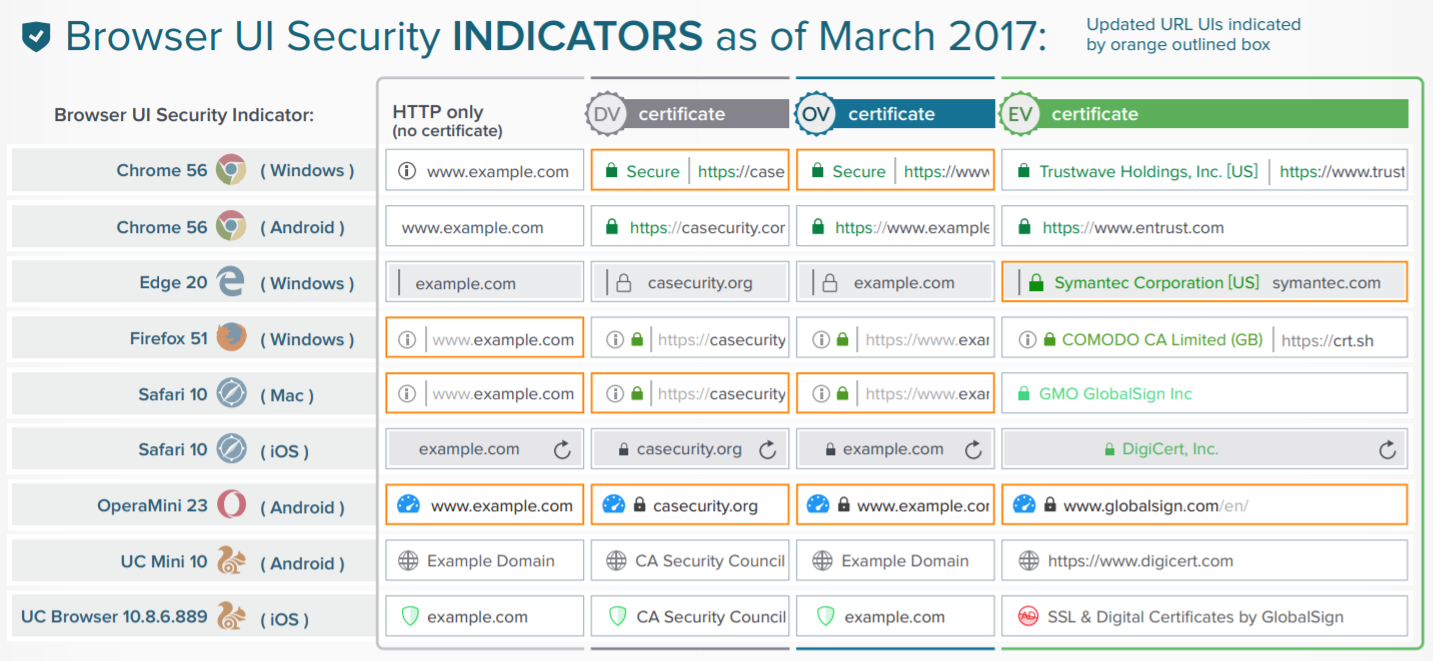

As noted above, the increase in encrypted phishing sites skyrocketed in 2018 due to browser requirements of https for every site to avoid UI warnings for users, and also due to the availability of anonymous, free, automated Domain Validated (DV) certificates to phishers. On top of that, browser actions, including the failure of browsers to coordinate on their UI security symbols, are making it harder and harder for users to know whether or not they are at a legitimate website. Here are examples:

- Browser UIs change frequently, and there is no coordination among browsers on what UI security indicators mean, causing user confusion

At one time, all browsers followed the same rules for their UI security indicators: a closed lock symbol for basic encryption, and the “green bar” with website owner identity information in the UI for Extended Validation (EV) websites where CAs had completed extensive identity confirmation. Users knew what the UI meant no matter which browser they used.

Unfortunately, browser unity on UI security indicators disappeared over the years, and most browsers are introducing new UI “looks” several times a year, resulting in the inability of users to understand what the UIs mean. Here’s a survey of browser UI security indicators from 2017 – not even SSL/TLS professionals can understand what they mean:

What’s more, browsers haven’t invested in user education to help them understand the constantly changing UIs. As a result, users are finding it increasingly difficult to know whether they’re at their intended website or a fake look-alike phishing site.

Browsers need to work together on common UI security indicators to be used in desktop and mobile environments, and work together with CAs to educate users on what the UIs mean to them.

- Google removes the EV UI security indicator in early 2019, leaving users with no way to know if they are at the real EV site for their bank or social media page, or at a fake DV phishing page – this will lead to more losses for users. Google already started down this road when it removed the distinct green UI in Chrome for EV websites and made everything a dull gray in Chrome 69 (September 2018). According to reports, Google will remove all EV website information from the Chrome UI as early as January 2019 with Chrome 72. This is extremely unfortunate, as studies show the vast majority of encrypted phishing (over 98 percent) occurs on anonymous DV websites. There is virtually no phishing on EV sites – but if the EV UI reduced is removed in January, users will have no way of knowing whether they are at a dangerous DV site or a safe EV site. With luck, the Google Chrome team will reconsider, and keep (and even improve) the current Chrome EV security indicators to help protect users from phishing.

The Ugly (A Potential Black Swan Event?)

Prediction: There will be a major state-sponsored attack on Certificate Transparency (CT) logs causing Internet outages.

This prediction may almost have happened already in December 2018 – see below.

Certificate Transparency (CT) is a Google-sponsored program requirement that all SSL/TLS certificates must be logged on CT logs in order to be trusted by Chrome. Most CAs log “pre-certificates” to CT logs first, before issuance of the actual certificate to a website owner, and then include proofs of logging in the signed certificate so that it will instantly be recognized as logged (trusted) by Chrome when a user navigates to the site. Google required CT logging for Chrome of all certificates starting on April 30, 2018, and Apple followed on October 15, 2018 for Safari. Mozilla says it will impose the requirement for Firefox in the future. Who operates CT logs? Basically, Google and a limited number of CAs and others, and the list of available CT logs changes frequently.

CT logging has been valuable in detecting errors in certificate details and helping CAs and browsers improve certificate issuance. CAs must repeatedly log the same pre-certificate to multiple CT logs for the certificate to be trusted by the browser (e.g., to three different logs for a two-year certificate), one of which must be a CT log operated by Google. This can cause delay in certificate issuance while the CA completes logging to multiple logs – and if one or more target logs are “down”, the CA must find other logs that will accept the pre-certificate. To date, many CT logs providers have been removed from Google’s approved CT program because they could not meet the uptime requirements to stay in the program. This has resulted in disruption in the available CT logs, meaning the list of available CT logs at any time may be uncertain.

Perhaps you already see the potential problem – requiring CT logging for all certificates across multiple logs (or else the certificates won’t be trusted in Chrome, Safari, and soon, Firefox) essentially makes CT logging a single point-of-failure for websites world-wide – after all, if a website can’t obtain or renew a certificate recognized as logged and therefore “trusted” by the browsers, that website will essentially be brought down and can no longer communicate with users.

How could this potential “black swan” event occur? By concentrated denial of service (DOS) attacks on key CT logs – this is the kind of attack that a state-sponsor could launch for the purpose of shutting down major websites around the world. A DOS attack on existing CT logs that lasted for days could mean that new websites could not be launched (because their certificates could not be CT logged), and existing websites could not obtain renewal certificates before their old certificates expire – taking down their sites. This potential attack vector increases as the validity period of certificates (the number of days certificates can be used) becomes shorter and shorter, because it increases the frequency of certificate replacement which in turn increases the opportunities to disrupt certificate replacement.

The possibility of such an attack seems more real by the apparent DOS attack on all Google CT logs for over an hour on November 30, 2018 – the post-mortem on the incident is still underway, and no public information is presently available. [1] Because Google’s CT program requires every certificate be logged to at least one Google CT log in order to be trusted in Chrome, an outage among all Google CT logs effectively means no certificates can be issued by any CA during such an outage.

Will such a black swan event as a major state-sponsored attack on Certificate Transparency (CT) logs cause Internet outages in 2019 – we don’t know, but given recent events it seems like a possibility. Stay tuned to CASC’s website for further details.