The media is full of stories about how phishing sites are moving rapidly to encryption using anonymous, free DV certificates they use to imitate login pages for popular sites, such as paypal.com.

As noted in the article PayPal Phishing Certificates Far More Prevalent than Previously Thought, more than 14,000 DV SSL certificates have been issued to PayPal phishing sites since the start of 2016. Based on a random sample, 96.7% of these certificates were intended for use on phishing sites.

A typical certificate will be for a lengthy URL such as login.paypal.com.phishingdomain.com where the user will see only the left side of the domain login.paypal.com in a compressed login window, and be tricked into giving the fraudster the user’s login information by mistake. These phishing sites are not limited to PayPal, but can be found for major banks, credit card companies, merchants, and social media sites as well.

But a recent well-written article in Forbes tells users how they can protect themselves against this exploit. In “That Website Padlock Won’t Protect You From Fraud”, Ian Morris carefully describes how these fake sites (encrypted by anonymous DV or Domain Validated certificates with no identity information) can be distinguished from the real login pages (encrypted by higher security EV or Extended Validation certificates that carefully verify the owners of the site):

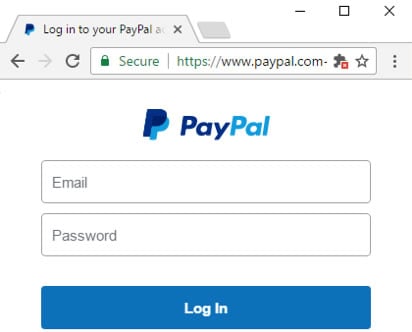

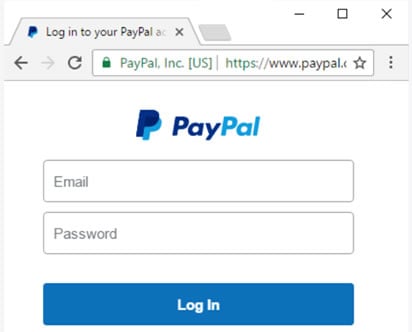

In my example, the fake PayPal login site had a security certificate, but if you carefully compare it to the real PayPal you’ll notice that the fake site says “Secure” in Google Chrome. The real PayPal site, however, replaces “Secure” with the name of the company, in PayPal’s case “PayPal, Inc. [US]”. This extra measure, called an Extended Validation Certificate, means the company you’re dealing with is actually the one you think you’re dealing with.

Morris points out that an EV or Extended Validation certificate on a website means the site’s identity was verified by non-automated means, and in this way is confirmed as genuine. Banks, credit card companies, and services like PayPal value security greatly, and so use EV certificates to protect users. Using an EV certificate to encrypt and identity a website like paypal.com prevents scammers from duplicating the PayPal site for a different domain and making it all look the same – the real and the fake login pages will have different UIs. But users need to know what to look for – and not all of them do. Morris concludes:

So looking for this [the EV certificate security indicator on a browser UI] on a secure site is a much better way to have confidence that you’re logging into a genuine place. As customers, we should be more keen to hassle companies to up their security game, especially if we feel unsafe when we’re entering our details – we’ve all got sites we feel this way about, I’m sure.

Here are two screen shots showing the difference between a fake DV PayPal.com login page, and the real EV Paypal.com login page, as described in Morris’ article:

| FAKE | REAL |

|---|---|

Certificate in Chrome. Actual site name for this example is paypal.com.summary-spport.com | PayPal login page secured by EV certificate in Chrome. Notice the EV UI indicator with confirmed website identity “PayPal, Inc. [US]” |

|  |

The lesson from this is that EV certificates, and their distinct UI display in the browsers, is more important than ever today for user protection. Browsers, Certification Authorities, and the media should work together to train users to look for the EV security indicator in the upper left of their screen before deciding to trust a website with their sensitive personal information.

Examples of the EV security indicator in the leading browsers today can be found here: https://casecurity.org/browser-ui-security-indicators/. For more information on the use of website identity in protecting users, see https://casecurity.org/identity/