Short answer: Government CAs can still be considered “trusted third parties,” provided that they follow the rules applicable to commercial CAs.

Introduction

On July 8 Google announced that it had discovered several unauthorized Google certificates issued by the National Informatics Centre of India. It noted that the Indian government CA’s certificates were in the Microsoft Root Store and used by programs on the Windows platform. The Firefox browser on Windows uses its own root store and didn’t have these CA certificates. Other platforms, such as Chrome OS, Android, iOS, and OS X, were not affected. See http://googleonlinesecurity.blogspot.com/2014/07/maintaining-digital-certificate-security.html

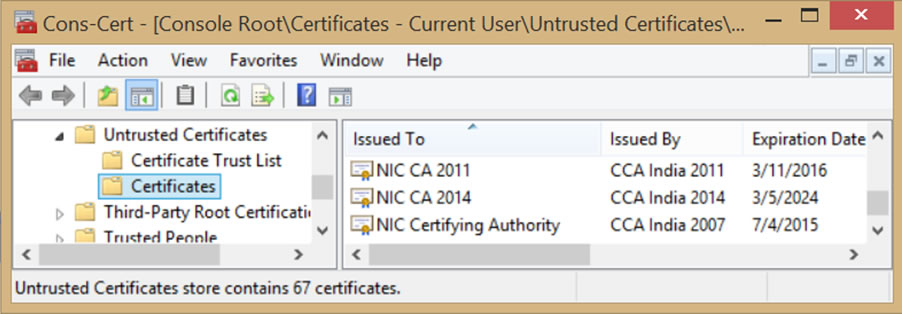

In response to this news, Microsoft updated its Certificate Trust List and removed the ability of three Indian CA certificates (NIC CA certificates issued in 2007, 2011, and 2014 by the Indian CCA) to issue any certificates, and it issued a Security Advisory https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/security/2982792.

This blog post discusses the following issues that have been raised as a result of this incident:

- What Happened?

- What security and operational practices did the Indian CA follow, and were such practices consistent with current industry practice?

- What kind of oversight or audit was in place with the Indian CA? How was this sufficient?

- What other actions have been taken by browsers in response to this breach?

- What should have been done, what should be done in the future, and what can we learn from this incident?

- What are CASC members doing to improve certificate trust?

What Happened?

There are things that we know happened, and there are things that we do not yet know, but on June 25 the first of several unauthorized SSL/TLS certificates were issued by India’s National Informatics Centre (NIC), which operates under the supervision of India’s Controller of Certifying Authorities (CCA). Both NIC and CCA are part of India’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.

On July 2, Google became aware of some of the unauthorized digital certificates because they had been issued for several Google domains because Google codes its own certificates inside of its Chrome browser. Google notified the NIC, the CCA, and Microsoft about the certificates, and it included those bad certificates in its CRLSet (Google’s way of blacklisting certificates). On July 3, the CCA advised Google that the three NIC CA certificates had been revoked, and Google updated its CRLSet to include them. (See Google Blog Post)

According to Microsoft’s Security Advisory, apparently 45 domain names were identified to be at risk, but the overall scope of misuse of the NIC’s subordinate CA certificates is unclear. We cannot tell from this Security Advisory whether someone other than NIC obtained a sub CA that was used to issue the SSL certificates; neither can we discern the degree of knowledge or intent by those responsible.

What security and operational practices did the Indian CA follow, and were such practices consistent with current industry practice?

It is interesting to note that the CCA’s Guidelines for the Issuance of SSL Certificates is only two pages long, http://cca.gov.in/cca/sites/default/files/SSL_Guidelines_APRIL_2013.pdf, which pales in comparison to the appropriate SSL certificate issuance practices published by Mozilla, the CA/Browser Forum, the WebTrust Task Force, and ETSI’s ESI Committee. NIC’s sparse assertion in its CPS that it queries domain registries before issuing SSL certificates seems inadequate as well. http://cca.gov.in/cca/sites/default/files/files/nicca%20cps%204.4.pdf.

At this early date, we do not have all of the information about the security measures that would have prevented this incident. Section 6.5.1 of the NIC’s CPS states that only authorized NICCA trusted personnel have access to the operating system and CA software, and other broad statements in sections 6.6 and 6.7 attempt to provide further assurance that file system integrity and logs are regularly checked, but these assertions are equivocal. It is also unclear which network security measures were in place. In January 2013 the CA/Browser Forum augmented then-current network security requirements with its Network and Certificate System Security Requirements. https://cabforum.org/network-security/. Many of the likely causes of this incident have been addressed already in the CA/Browser Forum’s network security document, including network authentication and access, system configuration controls, and logging, monitoring, and patching.

As noted by Microsoft, Google, and others, these certificates enable man-in-the-middle spying on end users. Of the 45 domain names listed by Microsoft, 18 belong to Google and 27 to Yahoo. The CASC believes this reveals an intent by the party controlling issuance of certificates to disrupt the security of public users. Whether the cause of the NIC certificate misissuance was internal or external is not as important as the fact that it happened — the end result speaks for itself. In other words, whatever happened, it certainly was not consistent with current industry practice.

What kind of oversight or audit was in place with the Indian CA? How was this sufficient?

According to documents attached to NIC’s request to be included in Mozilla’s trust store (Mozilla Bug #511380), NIC was independently audited by M/s CyberQ Consulting Pvt. Ltd. CyberQ’s 2010 audit statement asserts the audit met the CCA’s Guidelines and that those requirements are “equivalent to WebTrust 1.0”, but without more detailed information, it is difficult for the CASC to make that same conclusion. The NIC and the CCA are part of the same government department and the CCA approves the auditor. Section 31 of the “Information Technology Act 2000, Rules, Regulation & Guidelines” states the audit is supposed to include: “(i) security policy and planning; (ii) physical security; (iii) technology evaluation; (iv) Certifying Authority’s services administration; (v) relevant Certification Practice Statement; (vi) compliance to relevant Certification Practice Statement; (vii) contracts/agreements; (viii) regulations prescribed by the Controller; (ix) policy requirements of Certifying Authorities Rules, 2000” and at least twice per year, the CA is supposed to receive an “audit of the Security Policy, physical security and planning of its operation.”

Some browser root programs allow government CAs to submit government audits that are deemed “equivalent” to those used by private industry. This allowance is usually based on an understanding that a government CA is often required to use a government-mandated internal assessment scheme — something like NIST SP 800-53A or HMG Information Assurance Maturity Model and Assessment Framework. It is assumed that the audit criteria used by government auditors are at least comparable to WebTrust for CAs or ETSI TS 102 042. Second, they must have experience and skill in conducting IT security audits, using a variety of information security tools and techniques, an ability to evaluate the criteria of the applicable audit scheme, and a proficiency in examining PKI systems. Most importantly, these auditors need to be separately accountable for the exercise of their independent professional assessment — they must be sufficiently independent from the subject of the audit to perform the third-party attestation function. In the wake of this incident and others in the last few years, the CASC questions whether this “internal audit equivalency” advocated by government CAs is still a viable approach. It is CASC’s understanding that some root stores are re-visiting policies that have allowed “internal audit equivalency.”

What other actions have been taken by browsers in response to this recent breach?

As mentioned above, Microsoft moved the three NIC intermediate CA certificates onto its list of Untrusted Certificates — essentially revoking the embedded system trust for these certificates. These three NIC CAs were responsible for issuing the sub CA(s) that, in turn, issued the unauthorized SSL certificates.

Because the CCA had informed Google that “only 4 certificates” had been misissued (even though Google was aware of others), Google subsequently responded “[we] can only conclude that the scope of the breach is unknown,” and in light of that, it was limiting the India CCA root certificate to the following domains and subdomains: gov.in, nic.in, ac.in, rbi.org.in, bankofindia.co.in, ncode.in, and tcs.co.in. (See Google Blog Post).

We commend Microsoft and Google for taking these actions.

What should have been done, what should be done in the future, and what can we learn from this incident?

It is difficult for CASC to recommend additional changes to the oversight and regulation of government CAs when it is not clear which existing industry standards were implicated by this incident, and would have prevented it, had they been followed. It appears that unlike members of the CASC, the NIC did not follow any of the new industry guidelines adopted as a result of the Diginotar incident, such as the CA / Browser Forum’s Network and Certificate System Security Requirements, which includes audits and system testing that commercial CAs are required to have.

While there is no evidence that the misissued certificates were actually used in man-in-the-middle attacks, this incident further highlights why government CAs should be restricted and also why solutions like DANE (e.g. misissued certificates coupled with control over DNS) create a heightened risk that some government will attempt to spy on SSL/TLS communications. Regardless of whether governments should be trusted, the CASC believes that government CAs should meet the same standards as commercial CAs and that any future application for root inclusion by a government CA under an “equivalency scheme” should be examined with much greater scrutiny. And if government CAs cannot meet all current commercial standards, then those government CAs should be technically constrained to act only within the scope of their own countries’ domain names and issue certificates only for their own government domains.

What are CASC members doing to improve certificate trust?

Additional steps that CASC members are taking to improve certificate trust, in connection with the activities of other organizations, include:

- promoting OCSP stapling and must-staple – CAs already provide certificate revocation checking (CRLs) and certificate status information (OCSP), and OCSP stapling with must-staple is a newer and better method of quickly delivering certificate status information to end users and stopping man-in-the-middle attacks;

- implementing Certificate Transparency (CT) – CT is a Google initiative that requires early disclosure and logging of publicly trusted SSL/TLS certificates, which Google believes will provide an early warning of misissued certificates, similar to the way Google identifies misissued Google certificates;

- considering the Certificate Authority Authorization (CAA) record in DNS – because CAA allows a domain owner to advertise which CAs it trusts (thereby enabling additional detection of certificate misissuance); and

- publishing network and certificate system security requirements – which all public CAs are now being audited against.